Queer Animation Revolution: Analyzing cartoons' influence on the LGBTQ+ community

EASTERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY

Queer Animation Revolution:

Analyzing Cartoons’ Influence on the LGBTQ+ Community

Honors Thesis

Submitted

In Partial Fulfillment

Of The

Requirements of

HON 420 Spring 2025

By

Morgan Daniels

Faculty Mentor

Dr. Hannah James

College of Letters, Arts, and Social Sciences

Queer Animation Revolution:

Analyzing Cartoons’ Influence on the LGBTQ+ Community

Morgan Daniels

Dr. Hannah James

Abstract

The underrepresentation of LGBTQ+ and gender themes in media, most specifically children’s television/movies, has the dangerous potential to negatively influence societal and political mindsets regarding non-binary and queer individuals. The children of today are the leaders of tomorrow, so ensuring that kids are exposed to a diverse set of queer themes is essential in creating a society where all archetypes are accepted, regardless of sexuality or gender. Many current children’s cartoons are encouraging heteronormativity, which can lead to kids being confused about LGBTQ+ concepts when they’re ultimately exposed to them in the future. The few shows that have incorporated queer themes in the past have often done it in a crudely negative way by relying on harmful stereotypes to portray non-heterosexual/non-cisgendered individuals. A lack of queer visualization can also lead to young LGBTQ+ kids to feel lonely and misunderstood when they can’t find anyone they identify with on television. Fortunately, several cartoons have taken active approaches in incorporating anti-essentialist themes in their content so that all kids can be exposed to these ideologies in a positive way, as well as feel seen and understood by characters that represent them. Three of the most influential shows that have done this in a thoughtful and age-appropriate manner are The Legend of Korra, Adventure Time, and Steven Universe. This work will further analyze the use of cartoons to subvert hegemonic ideologies and support the queer animation revolution.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Table of Contents

Introduction

Table of Contents

List of Figures

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Queer Media Historically

Agents of Socialization & Representation

Queer Politics Under Siege

The Legend of Korra

Adventure Time

Steven Universe

Conclusion: Hope for the Future

List of Figures

Fig. 1: Bugs and Elmer Fudd kissing

Fig. 2: Ursula villain from The Little Mermaid

Fig. 3: Korra and Asami sincere moment

Fig. 4: Avatar: The Last Airbender ending versus The Legend of Korra ending

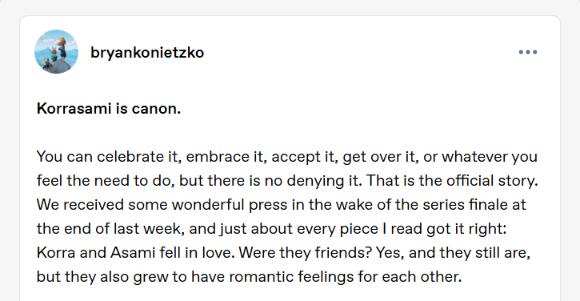

Fig. 5: Bryan Konietzko Twitter post

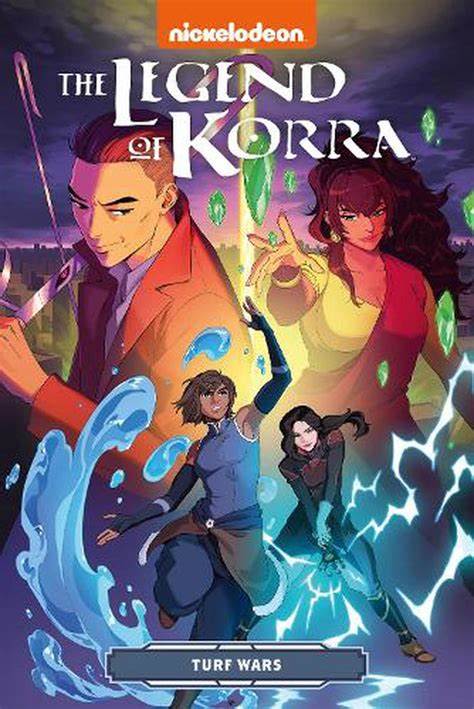

Fig. 6: The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars cover

Fig. 7: The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars page

Fig. 8: Korra and Asami kiss in The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars

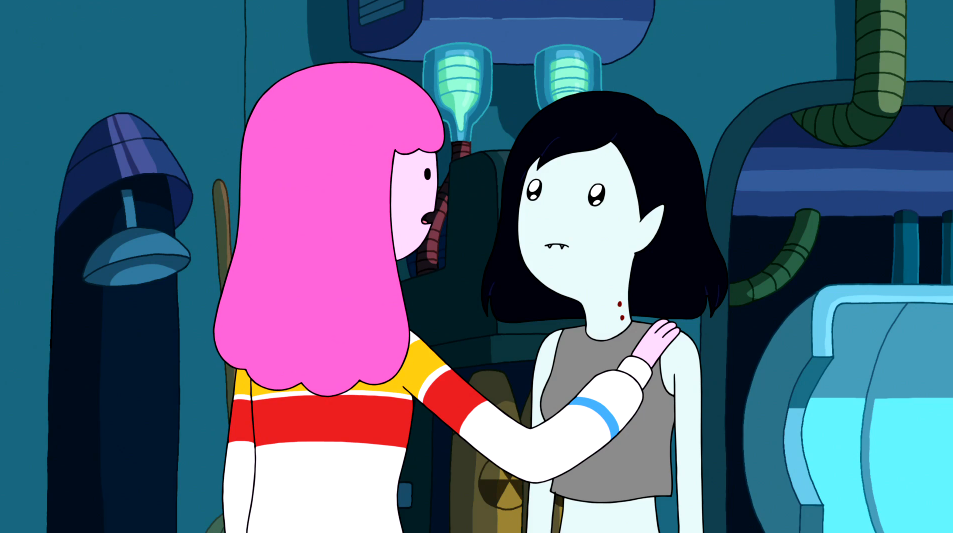

Fig. 9: Marceline the Vampire Queen (left) and Princess Bubblegum (right)

Fig. 10: Finn's hair

Fig. 11: "Friends Forever" episode

Fig. 12: "What Was Missing" song

Fig. 13: Frederator Studios recap clip

Fig. 14: Princess Bubblegum sniffs Marceline's shirt in "Sky Witch"

Fig. 15: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum intimate moment in "The Stakes: Part One"

Fig. 16: Princess Bubblegum asleep on Marceline in "Varmints

Fig. 17: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum kiss

Fig. 18: Princess Bubblegum and Marceline in Distant Lands

Fig. 19: Princess Bubblegum and Marceline in Distant Lands

Fig. 20: Ruby and Sapphire fuse for the first time in "The Answer"

Fig. 21: Ruby and Sapphire play baseball

Fig. 22: Ruby and Sapphire proposal

Fig. 23: Ruby and Sapphire wedding scene

Fig. 24: Steven performing on stage

Fig. 25: Steven and Connie fuse into Stevonnie

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Hannah James, my mentor, for guiding and supporting me through this process. It is with her time, dedication, and knowledge that I was able to create a piece of work that I am truly proud to present. I would also like to extend special thanks to my friends and family who listened to my constantly evolving theories and ideas. Most importantly, I dedicate this achievement to my sister, Alyssa. From our earliest years, she not only introduced me to the world of cartoons but also inspired me to embrace and advocate for progressive ideals. She has been a constant source of motivation throughout this entire project. Without her, this thesis would not have been possible.

Introduction

The early 1930s saw an influx in media censorship that would set the precedent for what is and isn’t acceptable on television for the next century. The Hollywood Production Code, or Hays Code, went into effect in 1934 and prohibited any depictions of homosexuality or ‘sex perversion’. The Code of Practices for Television Broadcasters was used from 1952 to 1983 and held similar standards and beliefs on homosexuality. Modern-day media is still reaping the negative effects of those codes and similar network decisions surrounding homosexuality, queerness, and gender. As a result, the LGBTQ+ community is lacking visibility on-screen, further encouraging heteronormativity in media. Heteronormativity is the “centering and normalizing of heterosexuality” or essentially the expectation that everyone should be heterosexual (Shaw and Lee, 2019, p. 222). Broader analysis, however, understands that television has the unparalleled power to influence thoughts, generate learning, and spark discussion. We often see this in young children’s shows with prosocial messages about sharing and being kind to others. This prosocial content has more recently been extended to include queer and gender themes in cartoons that are targeted at children aged around six to twelve (Bradley, 2017). Due to the progressive subject matter, however, many of these children’s shows appeal to tweens, teens, and adults alike. Children’s animation is a uniquely suited medium to approach topics of queer politics in that they intertwine valuable lessons into extraordinary plots that are simple to comprehend, which allows for LGBTQ+ subjects to be shared in ways that are subtle, yet effective to its viewers (Wright, 2018). Queer representation in the media can go a long way in shaping perspectives related to LGBTQ+ policies, which can make an impact on individuals both socially and politically. Furthermore, the importance of offering representation for young kids who seek to find themselves in the media they view cannot be understated. Children’s animated media provides an avenue to subvert heteronormative ideologies and present counter-narratives about queerness that are crucial in kids’ social development and understanding about the LGBTQ+ community. The queer animation revolution is the integration of positive LGBTQ+ representation and narratives into animated media, primarily children’s content, for its benefits in educating and influencing societal mindsets and political changes. Cartoons such as The Legend of Korra, Adventure Time, and Steven Universe have all taken active approaches in including topics of sexuality and gender identity in their content to overcome hegemonic barriers and encourage queer visibility, which will be analyzed in this work.

Queer Media Historically

In 1968, the Hollywood Production Code was removed and replaced by the still-standing Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating system that is still being used in some ways today (Palmer, 2020). The new system caused a shift in how queerness was represented in the media at that time, allowing some films to try and push the boundaries, albeit in tiny increments, of what they could produce in terms of sexuality and gender. Much of what was produced at this time ultimately resulted in harmful jokes that ridiculed homosexuality, in particular, and further ostracized the LGBTQ+ community. Through a lot of ups and downs, shows began to take beneficial steps towards supporting queerness. Since animation is already a medium that is accustomed to outlandish plots, outfits, drawings, and dialogues, it was a great place to stretch the boundaries of these political and societal restrictions. Two human men couldn’t kiss in a movie or wear a dress, but Bugs Bunny cross-dressing and kissing Elmer Fudd could be shrugged off as comedy. It was media companies and writers in the very late 2000s to the early 21st century that truly began to push the societal restrictions from the dated codes. Characters like Mojo Jojo and Him from Powerpuff Girls (1998-2004) on Cartoon Network included subtextual LGBTQ+ themes but were still hidden behind the villainous roles due to societal restrictions; this trend resulted in harmful connections between the LGBTQ+ community and 'dangerous' moral values. Despite the negative exposure, it was that slight bit of representation that aided and encouraged the inclusion of progressive themes in television. As a result, “television has proven itself both a documenter and an influencer when it comes to societal change” (Vogt, 2019, p. 1).

Figure 1: Bugs and Elmer Fudd kissing

Figure 1: Bugs and Elmer Fudd kissing

Agents of Socialization & Representation

Media, most specifically cartoons, are powerful agents of socialization (Mclnroy & Craig, 2016). They contain strong educating tools that are capable of socializing and instilling worldviews and ethics (Wright, 2018). Simpler than that, however, children retain what they’re repeatedly exposed to, and that knowledge can manifest itself in many ways. Have you ever seen a child who is obsessed with superheroes? Perhaps they want to watch the Batman cartoons every day, only use an Iron Man toothbrush, or even refuse to take off their Spider-Man costume. Those are examples of children manifesting what they see on television. That obsession stems from the desire to be the heroes they view on television. That is also why cartoons often contain prosocial messages that will instill positive lessons and ethics in children. That kid who wants to go to school in Spider-Man pajamas can likely quote the “with great power, comes great responsibility” line- a valuable message for many to know and learn. Furthermore, the media works as a director of ‘status quo’ by shaping societal norms and encouraging cultural values. According to Tony Kelso’s article in the Jornal of Homosexuality, numerous scholars have “convincingly argued that representations in the media have a socializing influence on young people’s development of their notions of self, whether in regard to race, gender, class, sexual orientation, or other identity categories,” (2015, p. 4). Similarly, Mclnroy and Craig argued in the Journal of Youth Studies that “media is the primary site of production for social knowledge regarding LGBT identities,” (2016, p. 2). Thus, a lack of LGBTQ+ representation not only encourages heteronormativity, but shapes mindsets on both personal and directed ideologies regarding queerness and gender-variance. Mclnroy and Craig further stated that harmful queer stereotypes remain prevalent in modern media, resulting in ongoing “societal homophobia and heterosexism” (2016 p. 3). In the same way that animated television upholds cultural norms, they also have the unparalleled ability to challenge them by serving as a tool of social change (Vogt, 2019). According to Vogt, “It has been shown that television allows creators to disseminate messages contrary to oppressive norms, which can spread positive messages of equality, compassion, and open-mindedness,” (2019, p. 3-4). That is a claim that will further be analyzed and supported throughout this work.

The homophobic and heteronormative ambiance created by the various codes and restrictions against television has further encouraged a society where queerness cannot be celebrated or acknowledged. In school and at home, children often do not have an equal chance at being taught or exposed to queer narratives. Heterosexuality is often presented as the only option in the classroom, as seen when students are only shown books, plays, and movies with exclusively straight characters and themes (Storz, 2022). As a result, kids are trained by heteronormative ideals in their everyday actions and thoughts about relationships and identity. This is apparent when children play an imaginative game of house and the parents they create are almost always a mother and father, never a same-sex couple. This is also seen when children’s toy companies produce items with an expected targeted gender in mind, thus training children to have specific sex-appropriated interests. When all the content children consume, such as movies, television, books, and games include cisgendered, heterosexual individuals, it’s hard to comprehend anti-essentialist concepts and be open and considerate once exposed to them. It is also important to note that queer representation is not an act of trying to incorporate ‘dangerous’ adult thoughts into children’s minds but is rather an avenue used to reflect real ideals and thoughts by the show creators into media. As noted in Vogt’s work, “Representation is the act of turning ideas into understandable words, images, and messages, but it goes beyond simply speaking or acting. Media are representations put into the world by creators,” (2019, p. 12). Furthermore, feeling underrepresented by pop culture can lead to a child questioning their identity and place in the world. Feeling seen by their favorite shows, worlds, and characters can improve confidence and encourage self-expression in young kids (Cook, 2018). Queer representation can be vital in the understanding of oneself and society.

Despite historically censoring queerness in media, recent times have showcased various networks, streaming services, and writers including more LGBTQ+ subjects into their work, though it has not always been done effectively or displayed in a positive light. From the start of television all the way up to current broadcasts, queer characters have very slowly become more frequent on TV, but mostly in a negative light. Confirmed and suggestively queer characters have been forced into harmful stereotypes or tropes that only work to negatively offend the LGBTQ+ community (Storz, 2017). Characters are portrayed overly flamboyant or ‘butch’, often given villainous roles, or killed off/sent away, thus never holding a recurring role. On the rare occurrence that a confirmed or suggestively queer relationship is portrayed on screen, it is likely that it will not represent a real or accurate relationship. The characters won’t be shown holding hands, kissing, lying in bed, or given any passionate, intimate moments. Same-sex relationships and heterosexual relationships do not get the same treatment in the media. Early depictions of homosexuals mainly consisted of child molesters, criminals, or poor representations of drag queens (Cook, 2018). The best representation of this in mainstream media can be seen in Disney’s problematic history of giving their villains suggestively queer themes. Characters like Ursula, Captain Hook, Gaston, and Scar are just a few on the long list of queer coded Disney villains, which even goes as recent as Turbo from Wreck It Ralph (2012). Another degrading tactic many film outlets use to draw in queer viewership for financial gain is queer baiting. This practice is when TV shows subtly hint that a character may be queer, but purposely never explicitly confirm it as a way of targeting queer consumers without offending heterosexual viewers (Storz, 2017). Queer baiting negatively impacts the LGBTQ+ community and uses homosexuality as a plot device to earn money. Conversely, programs will use queer coding in a similar manner, except this practice is more often when writers are being restrained by network codes but want to input subtle representation in the best ways they can. Queer coding is a step in the right direction but is proof that queer visibility in television has a lot of room for growth. This strategy is a way around censorship but is less than ideal because it often forces characters into harmful tropes and stereotypes. The Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD)’s annual Where We Are on TV report tracks the presence of LGBTQ characters for each TV season, and the 2023-2024 report counted 454 series regulars across primetime scripted broadcasted programming, which is a decrease from the following years. The previous two television seasons (2022-23 and 2021-22) both had around a hundred more recurring LGBTQ characters in their shows. It is important to keep in mind though, that while these characters are making appearances in shows, they are not always represented accurately as real human beings with multifaceted personalities, intense relationships, and complex feelings (Cook, 2018). It is still consistently a problem that shows are inaccurately portraying “normal” queer relationships and characters.

Figure 2: Ursula villain from The Little Mermaid

Figure 2: Ursula villain from The Little Mermaid

Queer Politics Under Siege

Finally, recent years have seen an influx of political bills and laws that are affecting the rights and reputations of the LGBTQ+ community. The 2022 “Don’t Say Gay” bill, a Florida law that has since encouraged action in other states, is a legislative attack on education about sexual orientation. The bill and its copycats censor classroom discussions about LGBTQ+ identities and subjects, as well as force school staff to contact parents if a child requests to go by a different name or pronoun(s). Other political agendas are banning and censoring books in libraries and classrooms that contain LGBTQ+ themes or characters. At the same time while some programs are taking an active approach to include important progressive themes in their content, other networks are doing the exact opposite. Conservative cartoons are being pushed out by “pro-American” networks, such as PragerU, that are encouraging conservative, non-progressive values. Leo and Layla and Tuttle Twins are two cartoons that take the viewers back in time through time-travel to retell important historical moments from a conservative standpoint, whilst suggesting racist and homophobic themes. These shows are centered around educating children and even vaguely follow some states’ elementary curriculum, proving that children are being taught heteronormative values and homophobic lessons in the classroom. While not children’s programming, The Charlie Kirk Show is another example of media pushing conservative ideals on others. Charlie Kirk is the founder of Turning Point USA, a national student movement that advocates instilling conservative politics on high school, college, and university campuses. On his podcast, Kirk has an episode titled "Protecting Your Kids from the Rainbow Mafia", in which he discusses how parents can evade “poisonous children content” and argues that the markets for kid’s books and cartoons are “flooded with gay and transgender propaganda.” The Charlie Kirk Show and Turning Point USA are both solid proof that anti-LGBTQ+ media are affecting queer politics (Kirk, 2025).

Cartoons are the most effective medium in encouraging queer animated revolution (Palmer, 2020). Palmer argues this in her thesis by stating that intertwining diverse characters and subject matters into children’s media gives the young audience images that they could identify with but also educates them on LGBTQ+ politics in a way that isn’t too overwhelming and is easy to comprehend. This is a statement that many other studies and researchers have agreed upon. As noted by Wright in her master’s thesis:

Imbuing cartoons with accessible theory is, in itself, a form of political practice. Cartoonists do not only imagine, envision, and describe new ontologies, but actively depict them in a way that demands participation; cartoons are a collaborative practice, utterly reliant on our ability to understand and act. In this regard, some of the most important—and impactful—queer praxis of today is occurring within the writing, creation, and production of children’s cartoons. (Wright, 2018, p. 5)

Without this knowledge, children may feel lost, confused in their own bodies, behind on societal subjects, or simply unaware of the real world around them. Fortunately, networks have been pushing out an increasing number of cartoons that subvert hegemonic beliefs and spark social discussion in terms of gender, identity, relationships, emotions and many more complex themes that children cannot be shielded from without falling behind in social development (Suby, 2019). Three animated programs that have been particularly revolutionary in this field include The Legend of Korra, Adventure Time, and Steven Universe. All these television shows have been broadcast by popular networks, done especially well in terms of viewership, and are targeted at young kids. All three shows have garnered a lot of popularity by both children and adult viewers and have actively influenced the queer animation revolution.

The Legend of Korra

In 2012, three whole years before same-sex marriage was legalized, Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino created a show that would pioneer queer representation in children’s entertainment by pushing against its restrictive network. The Legend of Korra (2012-2014) was the continuation of the popular Nickelodeon series, Avatar: The Last Airbender (2004-2008). Similar to its predecessor, The Legend of Korra included varying mature themes and lessons that are presented in, arguably, an age appropriate and thoughtful manner throughout the series. Among those messages were topics of death, terrorism, equality, freedom, self-discovery, and of course bisexuality. The Legend of Korra, though created in the U.S., incorporates influences from both Western and Eastern culture. Eastern style of animation, often known as anime if originated from Japan, is known to be much more fluid and open in terms of sexuality and gender (Bravo, 2022). Eastern culture is consistently more progressive in many aspects of life and that is represented in the media that is produced, such as video games, movies, and TV series. Eastern influence is seen in the suggestively sapphic relationship between two of The Legend of Korra’s main protagonists, Korra and Asami.

The Legend of Korra is set in a fictional world where the people are divided amongst four nations: the Water Tribe, Air Nomad, Earth Kingdom, and the Fire Nation. Within this universe, a select few are born with the power to “bend” or manipulate one of the four basic elements: water, earth, fire, and air. One special person, known as the Avatar, is capable of bending all four elements and is born with the duty to protect the world and maintain balance amongst the nations. The Avatar in this time period is a fiery, confident, and athletic teenager named Korra born from the Southern Water Tribe. The story follows Korra as she masters the four elements and works to create harmony amongst benders and non-benders. While on this Avatar journey, Korra meets two brothers, a firebender named Mako and an earthbender known as Bolin, as well as Asami, a non-bender and inventor. Together, the four of them work through the spiritual and political challenges within the universe, while simultaneously tackling the struggles that come with being a teenager. In the first two seasons, a complicated love triangle between Asami, Mako, and Korra occurs that causes emotional challenges and issues for the crew, but that is abandoned going into the third season as the characters ultimately decide that they’re better off as friends.

Though it is never confirmed in the animated series, there are several subtextual scenes that suggest a romantic relationship between Asami and Korra. While the two characters take a while to warm up to each other and navigate their feelings for Mako, they eventually become close and trusted friends. Several scenes depict the two hanging out for fun, having deep conversations, and going on adventures fighting villains together. In an intense season three finale, Korra is kidnapped and poisoned by one of the show’s main protagonists, Zaheer. While Korra and her friends ultimately defeat Zaheer and his team, Korra is left injured, unable to walk, and in extremely low health due to the poison. Following the battle, Korra is on bed rest due to the physical and psychological trauma she endured, causing her to shut her friends and family out emotionally. Asami helps nurse Korra back to health, and in one scene, has a deep conversation with Korra, promising to support her while she recovers. Korra ultimately decides to return to the Southern Water Tribe for a few weeks while she heals from her wounds and attempts to gain her strength back. Bolin, Mako, and Asami all promise to write her letters, and Asami even offers to stay with her at home, so she has some company. Korra denies Asami's offer, insisting that she needs some alone time to think and get back on her feet. It ultimately takes three years for Korra to return to Republic City with the rest of her friends, as she had severe PTSD from her fight with Zaheer and was struggling to use many of her Avatar powers. During that time, Korra only wrote back to Asami, despite receiving hundreds of letters from both Bolin and Mako. When Korra ultimately returns to Republic City, she spends a lot of time with Asami. The two of them have several hearts to hearts, and Korra even claims that she can only open up about these struggles with Asami. In one scene, Asami compliments Korra’s new haircut, in which the latter blushes and quickly looks away, which is suggestive of a crush in many animated shows.

Figure 3: Korra and Asami sincere moment

Figure 3: Korra and Asami sincere moment

On December 19, 2014, the monumental series finale of The Legend of Korra was released with the title “The Last Stand.” In this episode, Asami and Korra make the decision to go on a vacation to the Spirit World together, a parallel realm where spirits roam free. In the final scene, the two approach the glowing portal that will take them to this alternate reality. They share a quick smile, grasp hands, and slowly walk up to the portal. Together, they take one final step closer before turning to face each other, hands still connected as a yellow ray of light swallows them whole and fades to white at the top of their heads. The weight of that scene lies heavy, however, as their final pose directly mimics Avatar: The Last Airbender’s iconic closing. In the 2008 end scene, Aang and Katara face each other and hold hands in a pose that perfectly mirrors that of Asami and Korra, before finally embracing in a tight hug that is sealed with a kiss. The screen then zooms in close and swoops over the characters heads before being engulfed in a sea of white that officially closes the series, similar, if not identical, to how The Legend of Korra’s scene faded to a close. Finally, eerily similar romantic tunes were played during each clip with close-matching crescendos and tones. Thus, the implication of romantic intimacy is heavily alluded to by those matching poses, though the key and essential difference being Asami and Korra did not hug or kiss. The absence of romantic confirmation rings loudly to many.

Figure 4: Avatar: The Last Airbender ending versus The Legend of Korra ending

Figure 4: Avatar: The Last Airbender ending versus The Legend of Korra ending

A Vanity Fair article written by Joanna Robinson the morning after the series finale released called The Legend of Korra one of the most “subversive shows of 2014” and claimed that it could “have the power to change children’s TV forever” (2014). Robinson praised the series for its racial and gender diversity, as well as bravery in tackling mature religious and political themes. Robinson’s article put the most emphasis on the suggestively queer relationship between Korra and Asami. She noted that no other children’s show has pushed the gay envelope quite like The Legend of Korra. Just three days after “The Last Stand” aired, Bryan Konietzko confirmed the sapphic relationship in a blog post (Wright, 2018). Korrasami was the fan dubbed relationship name of Korra and Asami:

Figure 5: Bryan Konietzko Twitter post

Figure 5: Bryan Konietzko Twitter post

Korrasamni is canon. You can celebrate it, embrace it, accept it, get over it, or whatever you feel the need to do, but there is no denying it. That is the official story… Korra and Asami fell in love. (Konietzko, 2014)

“The Last Stand” is an episode representative of both great success and great failure. While The Legend of Korra created the most progressive and impactful scene in children’s animation at the time, it was also glaring proof that queer censorship remained strong, especially in children’s media. Konietzko’s confirmation of Korrasami had never been done before and elated many young viewers who desperately sought to see themselves in the media they consumed. However, many kids, adults, and fans alike didn’t seek out more information once they finished the show. For many, that scene didn’t scream gay in big letters, but was rather perceived as a platonic friendship. The most aggravating detail, however, is that this episode didn’t air on Nickelodeon’s cable TV channel. It was only released on Nick.com, Nickelodeon’s online streaming service. DiMartino and Konietzko claimed that network restraints wouldn’t allow them to make the relationship canon, but would support an ambiguous closing (Robinson, 2014). The series had been pulled off-air earlier that season for its dark material, which meant that the groundbreaking episode wasn’t available for all eyes to see. Many viewers didn’t seek out the show once it was pulled off cable, nor did every fan who wanted to watch have access to a laptop, phone, etc., in which they could stream the episodes. GLAAD’s annual reports state that LGBTQ+ characters are more frequently seen on shows released on streaming services than those aired on broadcast or cable television. Queer characters, themes, and relationships are able to avoid negative backlash and garner more support when they are being aired on streaming platforms due to the viewer selectivity of those shows. Furthermore, the Federal Communication Commission may subject broadcast shows to stricter regulations, as “indecent” content cannot be shown, except for late at night (Cook, 2018). Cook further argued in their study that:

Any show too far outside the mainstream on a broadcast show runs the risk of upsetting and alienating advertisers… The subscription model allows platforms to target niche audiences, while broadcast shows try to appeal to a wide audience across ages, location, and political demographics. Streaming and premium cable shows may even target the LGBT community. (Cook, 2018, p. 33)

Despite Korrasami being left to subtext in the animated cartoon, Dark Horse Books published The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars, the official comic series and three-part continuation of the The Legend of Korra (Wright, 2018). The comic begins right where the finale ends, with Asami and Korra entering the Spirit World. Korrasami is canon in The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars, as the series is bold in depicting sapphic love. Unlike many series that depict LGBTQ+ characters, Korra and Asami are given a tangible relationship where they kiss, hug, and represent real, honest love. There is no denying that The Legend of Korra set the precedent for the queer animation revolution in cartoons. Ending in 2014, the shows that followed this progressive series continued to push against the figurative gate that is heteronormativity. Despite being forced to queer code, The Legend of Korra opened a glimmer of hope that normative, restrictive ideologies could be challenged publicly in the form of children’s media.

Figure 8: Korra and Asami kiss in The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars

Figure 8: Korra and Asami kiss in The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars

Figure 6: The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars cover

Figure 6: The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars cover

Figure 7: The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars page

Figure 7: The Legend of Korra: Turf Wars page

Adventure Time

Another groundbreaking cartoon that attempted to subvert conservative mindsets and incorporate queer themes into its work was the popular Cartoon Network series, Adventure Time (2010-2018). Despite airing two years prior to The Legend of Korra, Adventure Time is more effective in its endeavors to challenge dominant views. Whereas the Nickelodeon series was forced to rely solely on subtext, Adventure Time confirmed their allegedly same-sex relationship in the final moments of the series. Many claim that Adventure Time paved the clearest pathway for future shows to confidently incorporate positive changes in the queer animation revolution (Vogt, 2019).

Adventure Time was created by animator and writer Pendelton Ward and aired on Cartoon Network from 2010 to 2018 with a total of 279 episodes over 10 seasons. The award-winning series is one of Cartoon Network’s most popular programs to date and appeals to a variety of age demographics. It was reported that the series pulled in an average of two to three million viewers an episode, making it one of the most watched children’s cartoons to date (Jane, 2015). On top of that, Adventure Time won nine Primetime Emmy awards from 2013 to 2018, as well as a variety of other accolades in both the U.S. and other countries. All this to say that Adventure Time is a well-known and highly praised series, in spite of its progressive inclusions. The cartoon takes place in the magical land of Ooo, a fantastical post-apocalyptic world that is populated by candy people, princesses, magical animals, and hundreds of other strange and outlandish creatures. The series focuses on a young human boy named Finn and his brother Jake, a shape-shifting dog. The two boys live in a large tree house and spend much of their time going on adventures, fighting evil, and saving princesses. Within the series are a diverse variety of fictional beings that team up and befriend the duo, such as a sentient, humanoid pink gum known as Princess Bubblegum, a half-demon vampire queen named Marceline, and an anthropomorphized game console called BMO. The series is undeniably creative, colorful, and eccentric in its theories, plots, and drawings. Most importantly, however, Adventure Time is liminal in representing themes of gender identity and expression, sexuality, and race/ethnicity. The series took full advantage of tackling and subverting many gender-related and queer-related paradigms, as well as discussing a variety of mature, emotional themes about childhood, growing up, love, found families, depression, grief, and many other sensitive topics (Jane, 2015). Adventure Time takes part in a story telling mode called narrative complexity, which allows its characters to gain social and emotional knowledge. More on that topic regarding character development and plotlines will be discussed later. While the length at which Adventure Time tackles gender theory cannot be fully unpacked in this thesis, it must be stated that this program is “an (unlikely) exemplar of a commercially successful children’s television program which depicts gender in a radically subversive and arguably liberatory manner” (Jane, 2015, p. 1). The longevity of Adventure Time likely has a lot to do with what the show was able to accomplish, as much of their liberal progression occurred during the later ends of the series. Over the eight-year run time, several political changes had been made, such as the legalization of same-sex marriage, as well as a shift in many social mindsets, which allowed Adventure Time to incorporate more representation with each new season. This show was perhaps the most influential in opening a pathway for future series to further tackle gender and queer inequalities in television.

Throughout the series, Adventure Time steadily builds upon the relationship between Princess Bubblegum and Marceline the Vampire Queen. The two characters individually challenge traditional gender roles in their actions, personality, and character archetypes. Princess “Bonnibel” Bubblegum, for example, is the ruler and creator of the Candy Kingdom and its people, making her the prime political figure within Ooo. She is cerebral in most instances but grows internally in many ways throughout the span of the show. Princess Bubblegum is a powerful figurehead, scientist, and inventor with unmatched intelligence and lots of ambition, though her morals are sometimes questionable. Her physical strength is nearly comparable to her IQ, and while she has been rescued by Finn and Jake on several occasions, she has equally been their savior in many battles (Jane, 2015). Despite being typically kind and compassionate, she has a darker, creepy side to her personality. She has little issue with experimenting on her subjects, finds humor in dark situations, and can be extremely hostile and aggressive at times. All this to say that Princess Bubblegum is an unorthodox female character, not just a pretty face or nerdy, book girl. Similarly, Marceline is loud, obnoxious, sarcastic, fun-loving, and rebellious. She is a punk-rock teenager with razor-sharp wit and a complex past. She loves pranks, music, and fighting, has a hot-temper, and is wildly stubborn. Her exterior is hard and flippant, a defense mechanism against her trauma, but internally she is vulnerable and lost. She is strong and independent, as seen when she defeats five powerful demons in “The Stakes” miniseries. Like Princess Bubblegum, Marceline’s gender archetype is non-patriarchal. They’re both unorthodox in how they’re represented, as many television series follow the platform that women, especially young girls, are delicate, poised, and weak. Rather, the two girls are strong, independent, and extremely powerful in their own rights.

Figure 9: Marceline the Vampire Queen (left) and Princess Bubblegum (right)

Figure 9: Marceline the Vampire Queen (left) and Princess Bubblegum (right)

Alongside them, the series is home to a variety of other diverse and nontraditional characters, specifically princesses, that challenge how society typically views royals. Some of the princesses are extraordinarily strong, some shy and awkward, others absurd and creepy, and several are voiced by men. Overall, the princesses are not set to one demographic, and they don’t match the oppressive “pretty, pink, princesses” stereotype. Most female characters in children’s television are mono-dimensional in that they are either dumb, super smart, damsels in distress, or crazy tough (Jane, 2015). While some shows will try to mend those gender stereotypes by depicting women as really intellectual or really strong, that isn’t an accurate representation of a normal individual. Ward attempted to rectify those concerns by creating a diverse set of female characters in the princesses of Ooo, most of which are given at least a little depth. Jane claims in her article that, “A female character whose defining characteristic is that they either weep or fight or make origami cranes or disco dance or possess ice ninja skills or beat box or play the flute, is unlikely to be as satisfying as a character like Finn who does all seven (as well as much else)” (Jane, 2015, p. 15). Ward uses this same approach in his gender expression of male characters. According to Jane, Adventure Time includes roughly an equal number of female and male characters in protagonists, antagonists, and minor roles, whereas females statistically only appear between a quarter and a half as frequently as males in children’s film and television (2015). The male characters in this series also defy gender bias in how society claims men should look and live. Finn, being the main protagonist in the cartoon, is a very unorthodox male character, especially for children’s media. While he is strong and powerful both physically and mentally, the typical signs of a masculine lead, he has moments where his interests and personality could be considered more feminine. Finn is a complex character that grows significantly throughout the ten seasons. He encompasses frailties that are far from the dominant tropes associated with masculine leads, such as when he spends half a season going through a depressive episode after losing his hand in battle. He has a high-pitched scream, long, luscious hair, is terrified of the ocean, and strongly expresses his “bromances” through acts of physical affection. In one episode, Finn happily and willingly becomes a surrogate mother for a baby bird, going as far to chew up food and regurgitate it into the bird’s mouth (Jane, 2015). Finn is a character that doesn’t represent society’s depiction of a “normal” male demographic. He is not always strong and not always dominant, traits that are not presented as unusual within the Adventure Time universe. Other male characters that represent a fluid approach to social roles are Jake, a doting father who happily cooks, cleans and sings about the tree house, as well as enjoys cross-dressing, occasionally wearing makeup, and role playing as women from time to time (Bradley, 2017). Jake was even born by his father, Joshua, who got pregnant after being infected by a shape-shifting alien. Like Finn, Jake is not threatened by his strong feelings towards other males, and often engages in close, emotional physical contact with other men. While he is in a long-term relationship with a female character dubbed Lady Rainicorn, Jake confessed in one episode that he had a crush on an ethereal male warrior named Billy. Gendered constraints truly have no platform in this cartoon.

Figure 10: Finn's hair

Figure 10: Finn's hair

Adventure Time is extremely effective in terms of offering equitable visions of gender to its viewers. Pushing that liberality, the series takes a non-essentialist approach in that gender identity is not fixed but rather fluid. Ward takes an almost transgressive action in including multiple recurring characters with ambiguous or androgynous genders. Characters in this show are often drawn in ways where they disrupt gendered readings altogether, creating an environment where anti-essentialist themes are always accepted, and labels irrelevant (Jane, 2015). Gender theory is supported repeatedly and sub-textually throughout the series to effectively normalize the ideology that gender, identity, and expression are not predetermined, and rather multidimensional. The sentient game console that lives with Finn and Jake, BMO, is often referred to as “he” and “she” in the series but is voiced by a woman. They have been confirmed genderless by Ward, given gender-neutral pronouns on many occasions, and hold a diverse set of interests that “typically” align with both sexes. BMO shares domestic duties with Jake, sings about being pregnant, falls in love with a bubble, plays soccer, and loves flowers. Similarly, Gunter the penguin, Ice King’s personal servant and best friend, is suggestively androgynous. Often referred to as “he”, Gunter is continuously given feminized pet names by Ice King, and even produces an egg in one episode, prompting Jake to shockingly question if the penguin is a woman. The instance is immediately brushed aside by Ice King, causing the episode to continue without question. Jane wrote in her article, “Like the rest of Ooo’s inhabitants, he (Jake) has better things to think about than the biological sex and gender orientations of the creatures who share his world” (2015, p. 12). Another genderqueer reference in the series is in season six, episode 32, when Ice King, the central protagonist of the series, utilizes a magician’s powers to give life to a simple lamp that he wanted to befriend. He is shocked, but elated, to discover that the lamp is a “lady” due to her newly produced feminine voice and large lips, but the object denies that claim by saying:

Figure 11: "Friends Forever" episode

Figure 11: "Friends Forever" episode

Well one isn’t purely defined by their sex or gender. I have yet to find out who I really am. I have freedom, no longer bound by the limits of my cord. Freedom to shape my reality, and in turn be shaped by it.

Arguably one of Adventure Time’s most impactful themes is its depiction of a canon lesbian couple. Princess Bubblegum and Marceline are alluded to have had a previous relationship throughout the early seasons of Adventure Time. Though most of it is left to subtext, there are certain scenes that clearly confirm that the two have a strong connection and care deeply for one another. It is important to note that both these characters are immortal in the Adventure Time universe. The initial pitch for the show did not depict them in a romantic relationship, but rather as friendly rivals, which led to limited engagement early in the series. Marceline and Princess Bubblegum’s first interaction is in season two in the episode “Go With Me”, in which Marceline repeatedly ruins Finn’s attempts at asking Princess Bubblegum out on a date. They only briefly interact in this episode, but a look of disgust washes over Princess Bubblegum’s face when she first sees Marceline, confirming that the two have met before. The true nature of their relationship is not revealed until the season three episode, “What was Missing.” In this episode, several of the main characters have their most prized possession stolen from them and locked behind a massive door that will only open by singing something true and honest. The door nearly opens after Marceline sings, “I’m sorry that I exist, I forget what landed me on your blacklist. But I shouldn’t have to be the one that makes up with you. So, why do I want to?” Princess Bubblegum listens wide eyed to the music, but Marceline ultimately trails off, flustered and upset by Princess Bubblegum staring so intently at her every word. When the door finally opened, it is revealed that Princess Bubblegum’s favorite item was Marceline’s T-shirt that the latter gave her as a gift a while ago. Princess Bubblegum clutches it close to her, claiming that it means a lot to her and that she wears it all the time as pajamas, which causes Marceline to blush. This episode confirms a previous, influential relationship between the two, which leads viewers to question why they feel so much agitation towards one another now. In the beginning of season three, a YouTube promotional series by Frederator Studios called “Mathematical!” released a recap clip of the episode that strongly suggested a romantic relationship between Marceline and Princess Bubblegum. The video says, “In this episode, Marceline hints that she might like Princess Bubblegum a little more than she likes to admit.” That recap clip was immediately met with intense controversy, causing the “Mathematical!” series to quickly be cancelled (Internet Archive, 2018).

Figure 12: "What Was Missing" song

Figure 12: "What Was Missing" song

Figure 13: Frederator Studios recap clip

Figure 13: Frederator Studios recap clip

The episode “Sky Witch” in season five creates more moments that clue to the girls having a deep bond for one another. In the opening scene, Princess Bubblegum is seen wearing the same T-shirt from Marceline. She inhales its scent deeply before opening her closet, revealing a photograph of Marceline and her taped to the inside. That episode then follows the two girls on an adventure to retrieve Marceline’s stolen childhood teddy bear from an evil witch. Princess Bubblegum ultimately ends up sacrificing the t-shirt in a trade for the teddy bear, as the sky witch deems the shirt to have more sentimental value.

Figure 14: Princess Bubblegum sniffs Marceline's shirt in "Sky Witch"

Figure 14: Princess Bubblegum sniffs Marceline's shirt in "Sky Witch"

The girls interact on occasion throughout the next handful of episodes, but it is in the seventh season when the Adventure Time team finally buckled down and focused on their growing bond. “Varmints” is one of the few episodes that place a looking glass on Marceline and Princess Bubblegum’s past. In this installment, Marceline is appalled to find that Princess Bubblegum has been overthrown as ruler of Candy Kingdom and is very offended that she didn’t inform Marceline of the shocking news. The two then find themselves in an underground tunnel, reminiscing on their past with one another when they come across remnants of their names spray painted on the wall. This episode strongly suggests that the two used to hold a very close bond and would often spend time together. Princess Bubblegum even admits that the stress and responsibilities of royalty caused her to push Marceline away. The episode closes with Marceline keeping watch of Princess Bubblegum’s new farm as the latter falls asleep on her, suggesting that Marceline wants to help lift some of the weight off Princess Bubblegum’s shoulder. Throughout the rest of the season, there are various subplots that further allude to a previous intimate relationship with one another, but also clearly confirm their close bond. In an eight-part miniseries that tackles Marceline’s past titled “The Stakes,” Marceline asks Princess Bubblegum to remove her vampire essence. Right before the procedure, Princess Bubblegum places a hand on Marceline’s shoulder, causing both their eyes to highlight with a soft expression, a position that mimics a declaration of love in many animated shows (Storz, 2022). Princess Bubblegum starts by saying, “Marceline, I am so very, very, very…” then she trails off, seemingly changing the subject by saying that she is excited to do the experiment. Marceline’s face visibly falls, suggesting that she was expecting a different statement. That scene is very indicative of Ward wanting to incorporate a sapphic relationship in Adventure Time but forcefully resorting to subtext so as to not rock the boat too much. Later in “The Stakes”, Marceline is poisoned, leading to an increasingly distressed Princess Bubblegum who is determined to save her. While in her coma, Marceline hallucinates an alternate reality where an aged Marceline is seemingly living out her life with Princess Bubblegum, in which the latter even kisses her forehead. Queer coding these two characters in tiny moments, scenes, and seemingly platonic discussions was the safest scenario for the cartoon, especially when the show still had a lot of plots to wrap up and couldn’t afford to be removed from cable.

Figure 15: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum moment in "The Stakes: Part One"

Figure 15: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum moment in "The Stakes: Part One"

Figure 16: Princess Bubblegum asleep on Marceline in "Varmints"

Figure 16: Princess Bubblegum asleep on Marceline in "Varmints"

Several more scenes are filtered into the final few seasons of the series, though nothing is labeled or confirmed until the series finale. This is very intentional, as confirming a queer relationship could’ve been quite damaging to Adventure Time and its revenue. In the final episode, “Come Along with Me,” Princess Bubblegum is crushed by a monster, causing Marceline to fear the worst. When it turns out Princess Bubblegum is not injured too badly, Marceline rushes to her side and embraces her in a tight hug. Marceline admits that she was scared to lose Princess Bubblegum again and the two have an intimate discussion that is sealed with a passionate kiss. Cloaked in childishness and eccentricity, Adventure Time was able to sub-textually, then canonly, incorporate a queer relationship that is representative of passion and love. According to reporter Andy Swift, this iconic kiss is the work of storyboard artist Hanna K. Nyströmthe. When given the layout for the series finale, the script had only indicated for the two to ‘have a moment’ (2018). Executive producer Adam Muto said that incorporating a kiss between the two had been an “ongoing conversation”, but ultimately never acted upon until that final scene (Swift, 2018). However, most of the credit should be given to storyboard artist Rebecca Sugar, a non-binary and bisexual creative that laid the groundwork for the sapphic couple, and slowly nurtured and evolved it over the years (Swift, 2018). This long-awaited kiss was inspiring to the many viewers, both LGBTQ+ and not, that yearned for confirmation of ‘Bubbline’ (the fan-given relationship name for Marceline and Princess Bubblegum). Adventure Time blurred gendered and heteronormative lines, creating a universe that was accepting not only of anti-essentialist ideologies, but of all beings. The series doesn’t allow room to question these patriarchal constraints, but rather inadvertently encourages the acceptance and understanding of every individual to make their own decisions about their life; a system that should be adopted more often in the real world.

Figure 17: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum kiss

Figure 17: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum kiss

According to a study by Chapman University graduate student Carl Suby, Cartoon Network gives “visibility to cultural groups who typically wouldn’t be seen on children’s television” (2019, p. 8). Suby’s study is particularly interesting because it references a theory by Todd Gitlin, American writer and political activist, that television networks use a slant to sell advertising space to products that they believe match their established socio-political leanings and will, in turn, maintain revenue (Suby, 2019). He describes the relationship between advertisers and television programs as an ecosystem that relies on one another to survive. Suby claims that Cartoon Network has a progressively liberal stance that puts emphasis on the representation of “various cultural identity politics” and their intersectionality (2019, p. 8). The program gives visibility to minority groups that aren’t typically represented in mainstream media, or more particularly, children’s television. Suby praises Cartoon Network’s success in consistently presenting their slant so often and effectively that it has sparked discussion and been singled out in many studies. The network incorporates racial and ethnic diversity in many of their works, as well as often challenges patriarchal views on gender expression and identity. Their success in this progressive slant is, in part, due to how they indirectly approach themes of cultural diversity, sexuality, gender, and intersectionality. Suby's thesis stated that, “Cartoon Network, consisting entirely of animated programs, makes use of characters who are aliens, anthropomorphized animals, and anthropomorphized objects alongside or in absence of human characters to code depictions of race throughout its ecosystem” (2019, p. 12). As a result, the shows can evade aggressive backlash from conservative viewers who feel less threatened by progressive themes being used on unrealistic and fictional characters. The network also avoids creating series that follow a reset format that have no structure or timeline, such as SpongeBob. Rather, Cartoon Network’s most popular and progressive shows have what Suby refers to as “narrative complexity,” which essentially gives the series’ plots that can be built on and referenced in each episode. This allows the characters, and in turn the viewers, to maintain the social education they gain between episodes. For all these efforts, Suby praises Cartoon Network in its use of a liberal slant and acknowledges the program’s societal impacts. He also claims that the Cartoon Network series that represents this slant most effectively and entirely is Adventure Time, thanks to its fervent, yet subtle incorporation of culturally diverse characters (2019).

Bubbline’s relationship was greatly expanded on in the HBO Max original series, Adventure Time: Distant Lands (2020-2021). Many of the unanswered questions about their relationship were discussed, such as why the two were angry at each other in the early seasons of the show. Many confirmed queer relationships in the media follow the buildup but never stay for the actual relationship. Books, TV shows, and movies will depict the ‘slow burn’ situations where two characters are crushing on each other and in the early stages of getting together but ultimately shield away from the actual confirmed relationship part: hiding the physical acts of same-sex love. In Adventure Time: Distant Lands, however, Bubbline is shown evidently and clearly in the prime of their relationship, happily in love and including displays of affection. This proud depiction of sapphic love would go down in history as one of the most progressive and groundbreaking queer animated couples; the series inspired individuals of all ages and worked to change oppressive mindsets worldwide.

Figure 18: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum in Distant Lands

Figure 18: Marceline and Princess Bubblegum in Distant Lands

Figure 19: Princess Bubblegum and Marceline in Distant Lands

Figure 19: Princess Bubblegum and Marceline in Distant Lands

Steven Universe

Just a week before the “Come Along with Me” kiss was broadcasted, another award-winning Cartoon Network program aired the very first same-sex proposal in any form of animated media (Swift, 2018). Steven Universe is a children’s cartoon created by Rebecca Sugar that aired from 2013 to 2018 and won the GLAAD Media Award in Outstanding Kids and Family Programming in 2019. Arguably the most queer and progressive of the three works being discussed, Steven Universe unashamedly allows for any and all LGBTQ+ themes to flourish and thrive. Whereas The Legend of Korra and Adventure Time struggled to fully express their queer characters for who they were intended to be, Steven Universe shows little issues in welcoming all forms of queerness and gender identity. Anti-essentialist concepts thrive in Steven Universe, which challenges the socialization of heteronormativity in young viewers. Steven Universe follows the life of a 14-year-old boy, Steven, who is an alien-human hybrid with supernatural powers. His mother, Rose Quartz, is the leader of the Crystal Gems, an extraterrestrial group of Gems who have rebelled against Gem Homeworld due to their strict customs and beliefs. Gems are literally powerful gemstones that present themselves in female, humanoid forms due to an intentional reflection of light, an important note to consider as that helps mask queer themes in inhuman beings. The remaining Crystal Gems, Pearl, Garnet, and Amethyst, live on Earth with Steven to teach him Gem culture, how to use his powers, and act as motherly guardians. Alongside the Crystal Gems, Steven helps protect Earth from Gem colonization and save humankind from annihilation. In Rose’s manifesto in Sugar’s book, Guide to the Crystal Gems, it states that the goals of the Crystal Gems are simple: “Fight for life on the planet Earth, defend all human beings, even the ones that you don’t understand, believe in love that is out of anyone’s control, and then risk everything for it!” (2015). Thus, Steven Universe encourages embracing differences and fighting for moral rightness.

Gem Homeworld is arguably an extreme representation of patriarchal society, as many of the hierarchical, stern principles have themes relating to real world issues. “Although Homeworld is a powerful matriarchy, it is shown to be a miserable place to live, due to its strict reliance on role assignment,” (Vogt, 2019). This is best seen in the societal expectations placed on Gem fusions. Fusions are the ultimate representation of a physical and emotional connection between Gems, though often only used for power and battle. In Gem Homeworld, however, fusion is only acceptable when done between Gems of the same type, or they’re otherwise viewed as taboo. One of Steven Universe's main protagonists is a tall, stoic Gem named Garnet who is the fusion of Gems Ruby and Sapphire. This makes Garnet quite literally a representation of sapphic love, as they fused out of passion, not power (Wright, 2018). That also means that Ruby and Sapphire's relationship is quite unusual, especially since Garnet tends to stay in fused form more often than not. “Additionally, the portrayal of Fusions in this manner mirrors our own world and the organization of sexualities into systems of power that encourage some activities while punishing and suppressing others, such as same-sex relationships,” (Storz, 2022, p. 36). In "The Answer," viewers get Ruby and Sapphire's backstory on how they met, and it is revealed that their love story is not accepted in Homeworld. When Ruby and Sapphire unintentionally fuse together for the first time, they are immediately rejected by other Gems on their home planet and nearly killed. “Fusions, then, subvert the ideologies of Homeworld by offering new ways of being that fall outside of the system” (Wright, 2018, p. 44). Steven Universe does an excellent job of making their fusion reflect a queer relationship. Gems are technically sexless but use she/her pronouns and present in ways that would typically be recognized as feminine, such as having high-pitched voices. In the way Ruby and Sapphire's relationship is not accepted on Homeworld, many queer relationships are not accepted in modern society. Despite the backlash, Ruby and Sapphire do not hide their love for one another, and they ultimately find friends (Rose, Pearl, Amethyst, and Steven) who accept them unconditionally. Later in the series, Steven and the Gems manage to change the attitudes and hegemonic beliefs about fusion on Gem Homeworld. This is an example of Steven Universe subverting harmful ideologies about queerness and community. The show suggests that society can adjust its teachings and learn inclusion, a powerful claim. "In Steven Universe, to be anti-queer is to be villainous, and only by accepting all Gems and Fusions, which represent queerness, are the antagonists welcomed by the heroes" (Storz, 2022, p. 37). That is an example of massive growth in the cartoon community that had yet to be seen in any children’s animated media.

Figure 20: Ruby and Sapphire fuse for first time in "The Answer"

Figure 20: Ruby and Sapphire fuse for first time in "The Answer"

Ruby and Sapphire's relationship is very clearly expressed throughout the entirety of the show. Not only is there a physical representation of their love, Garnet, but when the two are unfused, they simply cannot keep their hands off one another. When not fused, the two appear lost and always trying to get back to one another. In "Hit the Diamond," Ruby and Sapphire are forced to unfuse during a baseball game, but neither can focus as they are flirting the entire time. In order to win, Sapphire must hit a homerun but is too distracted looking at Ruby to make contact with the ball. Ruby solves this by saying that Sapphire can only look at her once she makes it home, which immediately inspires Sapphire to hit a home run. The two embrace at home plate and immediately fuse together, as their love for one another is too strong to stay apart. That shameless, uncontrollable passion for one another is what makes Steven Universe’s representation of a lesbian relationship so important. Ruby and Sapphire's relationship is anything but parody. It proves to the audience that queer relationships also represent genuine, honest love– an important fact for child viewers to understand. Ruby and Sapphire are groundbreaking in how queer couples are presented in children’s TV. Their intimacy is not shielded, but rather openly and repeatedly expressed throughout the series, which is a welcomed change.

Figure 21: Ruby and Sapphire play baseball

Figure 21: Ruby and Sapphire play baseball

Furthermore, Ruby and Sapphire deep dive into the difficulties of being in a long-term relationship. The two separate for a period to essentially think about how their relationship with one another has affected their personal identity and independence. They both go on journeys of self-discovery, only to ultimately end up deciding that their lives are best together. This leads to an emotional proposal scene, the first in any children’s TV show, in which Ruby declares that she wants Sapphire to marry her so that they can be together, even when apart. This scene was not only a monumental, irrevocable confirmation of their relationship, but an impactful visualization of queerness for viewers. Though it’d be a stretch, some could have argued that their relationship was purely platonic prior to that episode. In “Reunited,” Ruby and Sapphire officially get married and re-fuse as Garnet. During the wedding, the two not only subvert lesbian stereotypes, but offer themes of fluidity in gender expression. Typically, Ruby expresses more masculine traits, such as excelling in athletics, dressing in pants and a t-shirt, and even mimicking a western cowboy in one episode, whereas Sapphire has long hair, a quaint personality, and a long dress to suggest more femininity in her preferences. When getting married, however, Ruby is adorned in a long, white dress, while Sapphire dresses in a suit; that scene mirrors traditional butch/femme lesbian stereotypes, but reverses them, suggesting that neither character is bound by those gender roles (Storz, 2022). The entire wedding and reception is shown fully in the episode, all the way up to Ruby and Sapphire kissing at the end of the ceremony and fusing into Garnet. Ruby and Sapphire's relationship is proof of great strides in the queer animation revolution. Before this show, LGBTQ+ representation had been hidden in subtle scenes of prolonged eye contact, brief physical touches, and inexplicably implied love confessions. The incredible feat with Steven Universe is that there was none of that. Ruby and Sapphire were wholly gay, although the argument of being aliens and not technically female played a significant role in Cartoon Network allowing that. Still, the show still does an exemplary job in exposing children to differing forms of sexuality while allowing young queer kids to see aspects of themselves in powerful characters. "Steven Universe, though not perfect, is an amicable example of how children's cartoons can educate upcoming generations in what it means to defy expectations and go beyond labels” (Vogt, 2019, p. iii). Not every identity and sexuality in Steven Universe is clearly explained or known, but that has never stopped a character from being loved or accepted by the cartoon's heroes.

Figure 22: Ruby and Sapphire proposal

Figure 22: Ruby and Sapphire proposal

Figure 23: Ruby and Sapphire wedding scene

Figure 23: Ruby and Sapphire wedding scene

Despite the confidence in which Steven Universe depicted queerness, Sugar claimed that they had to be careful in what they could and couldn’t include in the series. In 2014, they pitched the episode “Jail Break,” which first revealed Garnet’s fusion and sub-textually confirmed the relationship between two suggestively female characters. Their biggest fear in making Ruby and Sapphire so clearly queer was that the show may be taken off air in conservative countries where kids needed to see these themes the most (Brown, 2020). Even before that, the show received a lot of pushbacks, and as a result, Sugar spent many years publicly avoiding clarification of Ruby and Sapphire’s relationship during interviews. Whereas Adventure Time didn’t initially pitch Marceline and Princess Bubblegum as a couple, Sugar said that they had clear intentions behind Steven Universe all along. They told the LA Times in an interview, “From the very beginning, one of my main goals was to find a way to create an interracial, queer-coded relationship that a whole generation of kids would see,” (Brown, 2020). There is even a small, suggestively queer crush associated with the Crystal Gem Pearl. Pearl is the most maternal and feminine presenting of all the Crystal Gems, as well as the one who had the closest relationship with Rose Quartz. Pearl has a complex fascination with Rose that is arguably a romantic crush. In the past, their relationship was very codependent, as they followed one another around the universe. They shared intimate physical touch, could achieve fusion, were each other's confidant and desired to always stay together. When Rose finally met Greg Universe, Steven’s father, and ultimately sacrificed her physical life form for Steven to be born, Pearl took it the hardest, even going as far as to resent Greg for much of the series. Though nothing is explicitly confirmed, Pearl and Rose had a strong connection that Pearl couldn’t easily forget, ultimately leading many to believe that they either had a past relationship or Pearl had an unrequited love. The progressive, anti-essentialist themes that Sugar grounded Steven Universe in didn’t stop at a lesbian relationship or crush, however, but greatly extended to gender identity and expression as well.

Steven Universe presented a variety of scenes, characters, and moments that challenge dominant gender discourse. One of the most prominent examples of this is in the un-patriarchal way that Steven presents himself. Steven is a young, powerful boy that enjoys protecting Earth and going on adventures–interests that are not unusual in male television heroes. Conversely, Steven’s personality and interests are socially perceived as feminine. To begin with, Steven’s dress and power mimics that of his mother, meaning that he often wears light pink, has a pink gemstone in his belly button, and can create pink shields and bubbles. He is a musical prodigy with perfect pitch, once even performing in a skirt, heels, and crop top on stage; an instance in which Steven was entirely comfortable and confident, as the audience cheered in excitement, entirely unfazed (“It Was Always Me”). Furthermore, Steven subverts harmful stereotypes about how young men should act. Many children’s animated shows reaffirm damaging beliefs that men should be strong, aggressive, unbeatable protectors who avoid discussing their feelings and internal struggles. This is not Steven's case at all, as he is in fact extremely emotional, having cried on numerous occasions throughout the series, and is typically quite vulnerable and open to his friends/family about his inner turmoil. One of Steven’s Gem abilities is known as Empathic Telepathy, a unique skill set that allows him to sense others' emotional state, even his enemies. This coincides with two of his protective powers, a shield and giant pink bubble, both of which protect and resist violence. Essentially, much of Steven’s powers are “rooted in a strength born of compassion, in a restorative empathy” (Wright, 2018, p. 41). These supernatural abilities relate to Steven’s personality, as he is extremely compassionate and accepting; he has never expressed judgement towards anyone, villain or not, and is always the first to encourage positivity and guidance. Steven’s unique, caring mindset is what fuels the series, as Sugar created a world where the socialization of the inhabitants on Gem Homeworld are unidimensional in their beliefs. Thus, Steven’s incomparable kindness encourages the antagonists to be more understanding towards life, love, Earth, humans, and so many other aspects of the universe. “Steven always tries to understand who someone is, and why they are the way they are, and tries to teach them what he believes in and why it works for him,” (Wright, 2018, p. 42). Steven is also quite literally part woman, as Rose still resides within him. Steven is a character that subverts societal expectations on how young boys should look, dress, and behave.

Figure 24: Steven performing on stage

Figure 24: Steven performing on stage

Similarly, many of the Gems, alongside various other characters throughout the series, challenge traditional gender identity and expression. As previously stated, Gems are inherently sexless, though they present themselves in feminine forms. Pearl mimics a stereotypical ballerina with her poised actions, ballet slipper, delicate movements, and porcelain skin. Garnet has a curvaceous body and wears variations of pink, while Amethyst has long, light purple hair with a trendy t-shirt style that shows what is suggestively a bra strap underneath. Despite those clearly societally labeled feminine features, each Gem is uniquely untraditional in their actions and interests. Vogt agreed, saying that "they each have their own unique array of attributes that defy what it means to be a female character, and they display these traits in ways that normalize female masculinity as a trait beyond binary expectations,” (Vogt, 2019, p. 28). All three of the Gems have powerful supernatural powers, repeatedly seen taking down monsters and lifting cars with ease. Furthermore, Pearl has short hair and loves science, Garnet is massively tall, and Amethyst has the immature humor of a little boy. This is a trend seen in the majority of the characters in Steven Universe; no character is entirely stereotypical or binary in their gender expression.

Alongside Steven and his gemstone friends, fusions also encourage themes of gender-progressive fluidity. Steven has the ability to fuse with his best friend, a young girl named Connie, to create a part-human, part-Gem individual called Stevonnie. This character is an exemplary challenge to gender norms and effectively educates viewers about androgyny. Stevonnie uses they/them pronouns and physically presents as neither man nor woman with a voice that could be argued as either masculine or feminine. Most importantly, no character questions Stevonnie’s identity or expects them to decide on a label. Even Kevin, a recurring human bully, does not mis-gender Stevonnie (Vogt, 2019). Stevonnie’s identity is entirely unfixed and accepted as a non-binary individual. Bradley further supported that claim by writing, “When transgender characters are invisible in mainstream media, the fact that a children’s show so casually introduces a character that confronts the gender binary is quite noteworthy,” (2017, p. 31).

Figure 25: Steven and Connie fuse into Stevonnie

Figure 25: Steven and Connie fuse into Stevonnie

Conclusion: Hope for the Future

There is a dire need right now in accessible education that is counter-hegemonic, positive and non-binary, especially as conservative agendas insist on silencing the LGBTQ+ community. Cloaked in discourse about “protecting children” and “upholding traditional values”, conservative beliefs have continuously censored queer content in the media, most specifically children’s television. These actions encourage heteronormativity by denying young viewers access to anti-essentialist ideologies that support fluidity and diversity. Visualization and exposure to those that are most different from ourselves, as well as those who are most identical to ourselves, is undeniably essential to youth’s emotional upbringing; the denial of these themes can result in the inability to understand progressive concepts, like queerness and gender identity. Furthermore, a lack of exposure to these concepts can create a deep-seated fear of difference and ultimately result in social ignorance. Queer cartoons play a vital role in fostering inclusivity, representation, and empathy, particularly for LGBTQ+ youth who have long been marginalized in mainstream media. Animated media such as The Legend of Korra, Adventure Time, and Steven Universe are all complex, multifaceted series that utilize a liberal slant to encourage progressive discussion and understanding. These shows provide affirming portrayals that validate diverse identities, challenge harmful stereotypes, and promote understanding among broader audiences. While queer representation in modern media has been on an uphill battle, gender and sexual conformity still remains the prevailing trend. By analyzing and praising these progressive works, more subversive children’s animation can confidently be produced and aired. In recent years, even after the finale of Steven Universe, several LGBTQ+ friendly kid’s cartoons have been created, such as She-Ra and the Princess of Power (2018-2020), Kipo Age of the Wonderbeast (2020), and the very popular The Owl House (2020-2023)–undeniable proof that pushing these societal constraints are slowly working. Ultimately, defending queer representation in media is not just about creative preferences, but rather a lifeline for those navigating the complexities of sexuality and identity, as well as a stand for basic human rights.

References

Banks, E. (2021). ‘The Hero Does Always Get the Girl’ an Exploration of Queer Representation in Child Centric American Animated Cartoons and Popular Culture with a Case Study on the Legend of Korra [Undergraduate honors thesis]. ResearchGate. www.researchgate.net/publication/351441412_’The_Hero_Does_Always_Get_the_Girl’_An_Exploration_of_Queer_Representation_in_Child_Centric_American_Animated_Cartoons_and_Popular_Culture_with_A_Case_Study_on_The_Legend_of_Korra.

Bradley, M. (2017). Girl Crush: Liminal Identities and Lesbian Love in Children’s Cartoons [Undergraduate thesis, Ursinus College]. Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/media_com_sum/12/.

Bravo, A. (2022). Content Analysis of LGBTQIA+ Representation in Anime and American Animation [Master’s thesis, California State University, Monterey Bay]. Digital Commons @ CSUMB. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2365&context=caps_thes_all

Brown, T. (2020, March 25). “Steven Universe” changed TV forever. For its creator, its queer themes were personal. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2020-03-25/steven-universe-rebecca-sugar-lgbtq-legacy

Bryan Konietzko. Tumblr. (2014, Dec. 23). https://bryankonietzko.tumblr.com/post/105916338157/korrasami-is-canon-you-can-celebrate-it-embrace

Cook, C. (2018). A Content Analysis of LGBT representation on broadcast and streaming television [Undergraduate honors thesis, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga]. UTC Scholar. https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses/?utm_source=scholar.utc.edu%2Fhonors-theses%2F128&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

GLAAD.org. (2024, April 30). Executive Summary – where we are on TV 2023-2024. Where We are on TV. https://glaad.org/whereweareontv23/methodology/.

Jane, Emma A. “‘Gunter’s a Woman?!’— Doing and Undoing Gender in Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time.” Journal of Children and Media, vol. 9, ch. 2, pp. 231–247, March 2016, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17482798.2015.1024002.

Kelso, Tony. Still Trapped in the U.S. Media’s Closet: Representations of Gender-Variant, Pre-Adolescent Children. Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 62, ch. 8, March 2015, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00918369.2015.1021634.

Kirk, C. (Host). (2025, March 27). Protecting Your Kids from the Mafia Rainbow. [Audio podcast episode]. In The Charlie Kirk Show.

Frederator Studios. Mathematical! By Frederator Studios for Adventure Time. Internet Archive. (2013). Mathematical! by Frederator Studios for Adventure Time : Frederator Studios : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive